By Katie Nash, UNC Health Foundation

Research evolves quickly and does not always follow a grand plan. For Aadra Bhatt, this flexibility led to finding her career passion.

An assistant professor in UNC School of Medicine’s Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Bhatt came to Chapel Hill in 2007 as a graduate student in microbiology and immunology. She never left.

“I just love it here,” Bhatt said. “I’ve felt so supported in my career at all stages, and when my current position was offered, I jumped on it because I can’t think of better colleagues or a better place to be.”

Although her training was in microbiology, Bhatt’s post-doctoral research involved chemical biology in the UNC Department of Chemistry. She became intrigued by gut bacteria, which are crucial triggers for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

“My investigation led me to think about the gut microbiome in a new way,” Bhatt said. “I wanted to see if we can manipulate the microbiome without antibiotics in order to help drugs work better for us by reducing side effects and increasing tolerability.”

A New Direction

Bhatt received a career development award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation after proposing to use gut bacteria of individuals who have IBD to develop personalized cures. Her primary goal is to figure out ways to predict detrimental or beneficial responses to certain drugs and treatments which are taken by individuals living with IBD.

“One of the manifestations of IBD seen outside of the intestine in many people is arthritis,” Bhatt said. “But they are unable to take common anti-inflammatory pain medications like ibuprofen because while they alleviate pain, they also exacerbate IBD.”

Bhatt proposed to unravel whether this side effect is a result of an individual’s microbiota composition. Certain bacterial enzymes can metabolize NSAIDs in such a way that it actually increases total exposure of NSAIDs to the gut. NSAIDs have unique properties that can cause damage to cell mitochondria. Bhatt’s hypothesis is that mitochondrial damage is one of the drivers of IBD symptoms.

The second goal of Bhatt’s research project is to discover whether she can use the gut bacteria of people with IBD as a “Trojan horse” that would allow bacteria to use drugs in a particular way.

“I’m interested in the possibility of developing a drug for IBD that is only active when it’s exposed to these bacterial enzymes,” Bhatt said. “This could be an approach where certain bacterial factors found only within an inflamed bowel could reactivate a drug in a very targeted and localized manner.”

Bhatt says the ability to localize therapy in the body is an important research point in drug development because some drugs for IBD are immunosuppressants, increasing a patient’s susceptibility to potentially dangerous infections such as COVID-19. By restricting the exposure of drugs beyond the intestines, side effects could be better controlled – and potentially eliminated.

Supporting Promising Work

Bhatt credits generous support from several donors such as the Layton family for helping her research flourish.

“I’m a junior investigator and really just getting my start – and it was certainly a slower start with the pandemic,” Bhatt said. “Gifts through the Foundation have helped me get on the path to developing personalized treatments for IBD and focus on the important science. It gives me peace of mind and allows me to have the help I need.”

Until February 2021, Bhatt’s lab was a lab of one. Donations through the UNC Health Foundation have allowed her to recruit a lab technician to increase research operations while also helping an early career researcher gain experience.

“When you make a gift, you not only support a junior investigator like me – you also open up opportunities to someone who will be in the next generation of scientists making discoveries,” Bhatt said. “I’ve learned so much about being a mentor and a leader.”

Donors to Bhatt’s work are impressed with her resourcefulness and collaborative spirit.

“When a family member was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, we wanted to figure out what we could do to help,” one donor said. “We really wanted to help someone take the next step in their research in this area, and Aadra seemed so close to it. She’s enthusiastic, positive and works with the researchers in her area to share ideas – to me, collaboration in science is so much more productive than competition, and she embodies that.”

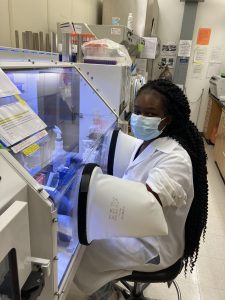

Bhatt’s lab technician, Glory Dan-Dukor, says her experience in the lab has helped establish her own career path.

“I’ve become comfortable in a lab space with things I’ve never worked with before,” Dan-Dukor said. “I’ve learned so much about gut microbiota and the diseases they contribute to, and how to work scientifically in a research environment. Because of the experience I’ve gained in this lab, I was able to get into graduate school here at UNC. I’m excited to be able to continue research at UNC and am grateful for the opportunity this has provided me to see what areas I can dive into. I’m very interested in how drugs affect the body – specifically cancer drugs – and how gut microbiota can impact their toxicity. With Aadra, I’ve learned there is so much interconnection between gut microbiota and many diseases and body functions.”

In addition to her own lab, Bhatt engages in another arm of research in the Mouse Phase I Unit at UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“My research mission is one shared by so many of my colleagues – we want to personalize treatments and help people feel better and get better,” Bhatt said. “We want to reduce the suffering from side effects that people face. We have all been touched by cancer, and through this work I’ve also met more and more people affected by IBD. It can be a very silent struggle.”

Bhatt says she is grateful that all areas of her research are propelled by the generosity of donors who are forward-thinking.

“A lot of times some of the ideas we’re working on are outside of the scope of what’s considered ‘normal,’ and philanthropy allows us to spread our creative wings and try some outside-of-the-box approaches. To see people so committed to science and realizing the importance of personal contributions to advance it is so personal and meaningful to me. Everyone has a story and wants to do their part, and that’s what inspires me.”

For more information on how to support this work and other initiatives in the Department of Medicine, please contact Beth Braxton, Director of Development, at beth_braxton@med.unc.edu.